Repopulating an Antique Land: Egypt’s Forbidding Western Desert

One hundred years ago, the British explorer WJ Harding King tried and failed to cross Egypt’s myth-laden Western Desert. Jack Shenker follows his footsteps into a once-isolated world on the cusp of transformation.

-Published in The National, Geographical and Internazionale

-The Western Desert, Egypt / January 2010

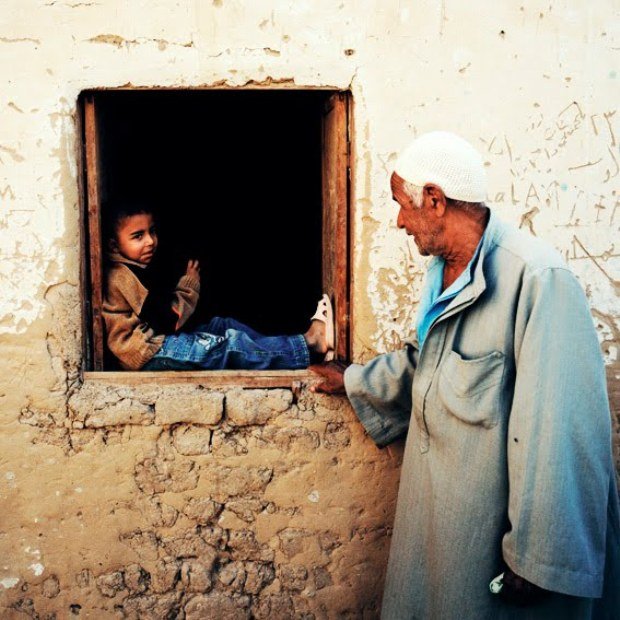

-Original photography by Jason Larkin, plus images, maps and sketches from Harding King's memoirs

There is a tree in the middle of Dakhla oasis that according to some locals possesses a soul. They call it the tree of Sheikh Adam, and it has stood for centuries at the heart of one million square miles of vast, almost waterless isolation, a space once considered to be amongst the most inhospitable places on the planet. It lies hundreds of miles from Egypt’s Nile Valley to the east, and hundreds of miles from the Libyan border to the west. If you climb the small hill on which the tree is perched and peer out in either direction you’ll be hard-placed to see anything beyond sand dunes, some up to 500ft tall, marching unceasingly across the void. A British scientist who reached this spot in 1910 declared the tree to be a symbol of everything magical about the desert, “a land where afrits, ghuls, genii and all the other creatures of native superstitions are matters of everyday occurrence; where lost oases and enchanted cities lie in the desert sands.”

A century later, the tree remains. But today it symbolises a new reality. Fenced in by a 10ft high steel fence and overshadowed by a gleaming red and white communications tower, the enchanted acacia stands in 2010 as testament to one of the most astounding environmental transformations taking place anywhere on earth. It now juts out of a new military installation, one of hundreds which are overseeing the wholesale integration of the desert into the modern Egyptian state. A land of lost legends – where the ancient god of chaos, Seth, was sent into exile, and where 50,000 hardened soldiers of the Persian pharaoh Cambyses were swallowed up en masse by a sandstorm, never to be seen again – is being slowly turned, house by house, road by road, city by city, into the most improbable of solutions to the country’s rapidly-escalating population crisis. Through a technological soup of new reservoirs, expensive pumping stations and irrigation canals that crawl hundreds of miles through 40 degree sunshine, the Cairo-based government is aiming to turn over three million acres of arid ground into green farmland over the next decade, and provide a home for up to 19 million Egyptians along the way. Nothing less than an entire new valley of life is being scheduled to rise, phoenix-like, from the sand.

It will be the country’s biggest construction project since the pyramids, cost billions and billions of dollars, and according to many scientists, is so bold as to be completely unachievable. And yet it is underway – metamorphosing beyond all recognition the ‘untouched’ wilderness that the British scientist stepped into one hundred years ago. His name was W.J. Harding-King, and the subject of his enquiry was North Africa’s Western Desert, which forms the eastern fringe of the Sahara and spans parts of Egypt, Libya and Sudan. On the centenary of his remarkable expedition, I followed in his footsteps to find a forgotten hinterland in flux.

***

“Romance,” observed Harding-King at the start of a candid memoir of his voyage into the dunes, “is merely the degenerate offspring of imagination and ignorance. There can be few parts of the world where one is so much up against hard cold facts as one is in the desert.” Quixotic narration was never the hallmark of this Cambridge-educated adventurer, and the rest of the book’s 336 pages have little time for the saccharine prose which Harding-King believed was typical of so many other depictions of the dunes. His desert was one which blazed with cold scientific detachment and colonial righteousness, and only rarely lapsed into histrionics.

The forty year old launched his epic three-year immersion in the Western Desert at the behest of the Royal Geographic Society in London, of which he was a fellow. Ostensibly, his brief was to categorise sand dunes, something Harding-King had already been doing in other parts of Saharan Africa; in reality the goal was imperial pride. Others Europeans, including the great German geographer Friedrich Rohlfs, had tackled the same terrain in the past, but none had yet succeeded in crossing the desert’s entire ocean of ‘impassable’ sand dunes and making it to the Libyan oasis of Kufara on the other side. Harding-King’s own stab at the challenge came as the ‘golden period’ for European exploration of Africa’s so-called hidden corners was drawing to a close, with the drumbeat of imminent world war already thudding softly in the background.

It was an attempt riddled with drama, disaster and betrayal, the climax of which came deep within the sand sea when it emerged that Harding-King’s entire caravan of servants were secret agents of a hostile Islamic sect. It was also an expedition marked by a series of breathtakingly orientalist assumptions, the flaws of which were not apparent to this most meticulous of Edwardian geographers. And yet despite its problematic nature, Harding-King’s journey into the Western Desert– and particularly his observations on the people who called it their home – provides a remarkable insight into this fast-mutating corner of the world today.

Back in 1910 the Western Desert was a space marked by its distance, both literal and metaphorical, from the hectic rhythms and state control of the bustling Nile Valley. Today the opposite is true. Every week more and more of the Nile Valley arrives on the desert’s doorstep, as the government-run ‘New Valley Project’ gradually materialises and the apparatus of a previously-absent state unfurls in the wilderness. The project is an ambitious answer to a desperate question faced by the Arab World’s largest country: what to do with the one million extra citizens that are being added to the population count every nine months, and how to feed them all when the nation’s already overstretched breadbasket – the Nile Delta, one of the most fertile places on the planet – is being slowly eroded by rising sea levels.

The project is on display everywhere. Travel the same trails that Harding-King took a hundred years ago and you will find that near-impassable dunes have been replaced by near-impassable police checkpoints, manned by sweating officers sporting impossibly thick khaki jumpers. Along the way, pylons dot the landscape; almost every conurbation now boasts a solar-powered phone mast. ‘You are connected!’ each one seems to scream, ‘You are no longer alone!’ The older generation in the desert oases may still refer to Nile Valley Egyptians as ‘foreigners’, but the fate of the tree of Sheikh Adam is a reminder that the Egyptian state is finally here, and here to stay. In the modern, hooked-up world of the Western Desert, there is little place for trees with souls.

***

It’s tempting to characterise the traditional residents of the Western Desert’s oases – a melting pot of tribal descendants from the Tebu, Tuareg and Berber peoples, and Bedouin Arabs originating from the Gulf – in a familiar mould: as a community struggling to retain its independence as the iron fist of the state reaches imposingly into their lands. But the truth is far more complex. As Harding-King himself discovered, the desert communities have always faced encroachment from outsiders ever since its five main oases were first cultivated during Pharaonic times. Criss-crossed at different times by slave caravan trails, Roman garrisons and even barbed wire fences erected by Mussolini, this land is well-accustomed to external influences, its people a product of a dynamic process of interaction with the rest of the world. Migrants may be arriving in unprecedented waves today, but the endless cycle of tension and fusion with alien forces is nothing new.

In 1909, Harding-King was thrown into this cycle through his dealings with the Sanusi people, “dervishes whose character ... was of a most uncompromising nature towards all non-Mohammedans.” At the time these desert dwellers who, as fellow explorer Ahmed Hassanein explained, were “not a race nor a country nor a political entity nor a religion, [but] have however some of the characteristics of all four,” were at the height of their power and controlled large tracts of the desert that Harding-King was venturing into. “They had the undesirable peculiarity – from a traveller’s point of view – of regarding the part of the Libyan Desert into which I was proposing to go as their private property,” he reflected, “and of resenting most strongly – to put it mildly – all attempts to penetrate their strongholds.”

Harding-King was fascinated and perplexed by these devout Muslims, who built white-brick monasteries (zawias) in the sand, refused to smoke, and eventually came close to killing him after it emerged that his travelling party was composed exclusively of zealous underlings of the Sanusi Grand Sheikh, all of whom had pledged to thwart the expedition. Like many explorers who had walked this ground before him, Harding-King saw those who lived in the desert as merely an accessory to his grand project, and catalogued them and their habits as impassively as he did his camel species and rock samples; spurred on by a seemingly divine right to exploration, it never occurred to him that those occupying this vast space did not share in his desire to pick over them and have the findings presented in prestigious scientific journals in London. He therefore missed the magnetism of the Sanusi, oblivious that locals might be grateful to these warriors who fought to keep Europeans, be they armies or explorers, out of the sand.

One of Harding-King’s most in-depth encounters with the Sanusi came in Dakhla, where he took tea with Sheikh Mohammed el-Mawhub, a Libyan who had been sent to the oasis to convert the locals. The explorer then spent the night at the family farm, built on a tiny village founded by the Sheikh. Harding-King, like the native officials around him, stood somewhat in awe at the great Sheikh el-Mawhub. The latter’s quiet authority, vast learning and ‘ceremonious manners’ appeared symbolic of the potency of the Sanusi as a whole, standing as they were on the brink of a monumental military showdown against both the British and Italian empires, who were closing in on their territory from Egypt and Libya respectively. The Sheikh even encouraged Harding-King to move into his zawia and learn Arabic with him (“I own I was tempted,” admitted the Brit). Yet in reality the Sanusi’s power was about to fade away. Just a few years after Harding-King’s afternoon with the Sheikh, British soldiers burst into his village and demanded the Sheikh be handed over. The old man had already escaped to Cairo where he was lying on his death bed; in retaliation the soldiers burnt down his house and imprisoned his children.

Today Ahmed Idris Mohammed el-Mawhub, the Sheikh’s 69 year old grandson, is one of the few oasis-dwellers left for whom the word Sanusi still has any meaning. By the 1920s, when the Sheikh’s sons finally returned to the village founded by their father, the Sanusi movement had been crushed militarily by its enemies and local appetite for Sanusi religious doctrines had sapped. “Only we are left as memories of that time,” says Ahmed as he looks out over his grandfather’s town, now home to 2,800 people. “People don’t need them anymore, so they don’t think about them. Times have changed; we’re people of Egypt now and the Sanusi have become an anachronism.” Yet amongst those old enough to remember tales of the Sanusi, a residual nostalgia remains; the Sanusi styled themselves as protectors of the desert’s purity and its people, despite regularly launching brutal raids on villages in order to seize supplies. It’s an impulse which Harding-King couldn’t understand, but which today is being felt by some more keenly than ever.

To see why, one need look no further than Farafra, the most isolated of the oases and the latest to be targeted by the government’s mammoth resettlement plans. Harding-King was surrounded by “surly and unpleasant” natives when he arrived here a hundred years ago; “Farafra being the least known of the Egyptian oases, the advent of a European was an event of such rare occurrence that the natives had evidently decided to make the best of it,” he remarked. Looking out from the precarious mud brick towers of Qasr Farafra, which back then was the region’s only village, Harding-King would have seen nothing but the staggering emptiness of a 125-mile long depression. Today, the view is very different.

Encouraged by a government package which involves a heavily-subsidised, interest-free house, up to twenty feddans of free land, free water and free electricity for five years plus a monthly stipend of free flour, cheese, sugar and rice, migrants from the Nile Valley are arriving in their thousands. The depression is now striking not for its emptiness but for its activity; with new wells being sunk all over the landscape and dozens of new communities springing up out of nowhere, the whole oasis bears more resemblance to an 1850s Californian gold rush town than it does to Harding-King’s memories of “a poor little place with a total population of about five hundred and fifty inhabitants.”

The newcomers may not be Europeans, but they are not people of the desert either; rather they are from the Nile Valley – stretching from Alexandria in the north to Aswan in the south – and their arrival has had a profound impact on the life of the oasis. Abdel Raba Abu Noor was born in 1929 in Cairo and moved out to Qasr Farafra when he was just two years old. Before Nasser’s 1952 revolution – news of which was heard on the single village radio – the only non-locals he ever saw were the traders he and his father encountered on their thrice-yearly camel trek to Asyut to sell dates, a mission which took ten days. “This was the only village in the oasis back then,” he reflects today. “We were unimportant. Now everyone is coming and we even have presidents come out to visit us.”

Abu Noor speaks proudly of the growing status of his hometown, for so long a forgotten corner of this vast country. The centre of the village may still resemble an industrial wasteland but the fringes have a new-build, suburban feel about them as new arrivals begin laying down their roots, sprucing up their houses whilst their children explore the dusty alleys by bicycle. Sitting below a framed portrait of President Mubarak in his grey-walled guest room, Abu Noor is quick to insist that despite the unpredictable social mix that has been grafted en masse onto this tiny conurbation, village life remains harmonious. “Of course the character has changed, but it’s for the better,” he insists. “There’s very little fighting.”

Others, though, tell a different story. Talk generally about migration to the old residents of the oases and the reaction tends to be positive, if somewhat indifferent. But when specific problems are mentioned – local land disputes, petty thefts, family quarrels – resentment against the newcomers quickly boils to the fore. Back in Mawhub 200 miles away, Osama Ahmed Mohammed, a great-grandson of the old Sanusi Sheikh, puts the blame for the Western Desert’s problems squarely on the shoulders of ‘Egyptians’ pouring in as part of the resettlement programme. “The problems come with them,” he argues, “because traditions change and the confidence we have in each other as members of a community changes with them. Everything is based on our shared history and once that is diluted, everything is lost.”

Rather than naked intolerance to outsiders, what really characterises the new Western Desert – amongst both traditional dwellers and those who have only recently set up life in the void – is insecurity over identity, a concept constantly being contested as new people, ideas and money fly west from the Nile. Harding-King noted some of this vacillation a hundred years ago, watching as oasis farmers juggled pagan folk customs with Islamic doctrine and fitted local power hierarchies into the political diktats of colonialism. Today there is a yet another element of uncertainty, in the shape of new towns and villages springing up from the sand which are being built entirely from scratch. Here in the frontier provinces, families hailing from all over Egypt are having to carve a cohesive communal personality for themselves out of thin air.

Abu Minqar has the questionable honour of being one of the most isolated communities in the whole of Egypt. First mapped by Harding-King himself, the uninhabited mini-oasis was the location of the explorer’s ultimate showdown with his Sanusi enemies; today, this new town serves as a far-flung microcosm for both the good and bad aspects of the desert’s dramatic makeover. As close to Libya as it is to the Nile Valley, Abu Minqar boasted a population of precisely zero in 1987; today there are 4,000 people living there, the product first of a government programme designed to allocate new land for ‘landless’ Egyptians (children whose family farmland had been divided up into unworkably small plots through the Islamic inheritance system), and then of the Mubarak graduate programme, which encouraged state university students to build a fresh life in the New Valley.

It’s only when the sun rises over Abu Minqar that one realises just how distant this previously-unremembered patch of desert is; hearing the cocks crowing and donkeys braying as hundreds of square miles of wilderness reveal themselves in the dawn light is an eerie experience. So is watching the morning assembly at one of the town’s three new schools; children line three sides of a dusty playing field and respond as a 13 year old boy belts out nationalistic slogans whilst standing to attention in front of the Egyptian flag. The chants ring out enthusiastically, before being engulfed by the silence and stillness pressing in on every side. The school children don’t look bored or disinterested at the ceremony. In fact, if anything they look zealous; as the first generation to be born in this previously-deserted land, they know they are at the forefront of a new Egypt, far removed from the Nile Valley towns their parents hail from. Ali Abdu, the manager of a motorcycle shop in the village, says that for the first time since he moved here, a sense of identity personal to Abu Minqar is developing. “Now we’re proud to say we’re from Abu Minqar,” says the 35 year old, who was born in Dakhla oasis but whose parents came from Upper Egypt.

It’s a far cry from the day Harding-King arrived, finding nothing but a loose scattering of stones pointing towards Mecca. Yet amidst the profusion of new wells and irrigation canals pulsing excitedly through the sand, some nagging questions about Abu Minqar remain unanswered. Despite the generous subsidies package on offer to newcomers, scepticism about the government remains high. “The government implores people to come out here, but then only provides the most basic infrastructure in terms of everything from social services to agriculture,” says Tina Jaskolski, a researcher at the American University in Cairo’s ‘Desert Development Centre’ which is operating a major project in the village. “We only get running water in the taps three hours a day, and this is one of the last places in Egypt without 24-hour electricity. People here are so far removed from even the local centre of politics, never mind Cairo, that they just feel ignored.” Many arrive in Abu Minqar determined to embody the frontier spirit – in Dr Jaskolski’s words, “they come on purpose to build a new life and they want the community to succeed and improve” – only to leave again after a few years because of the hardships faced out in this strange slice of Egypt, an unknown speck on the national psyche and at the same time supposedly at the heart of its future.

And disillusionment amongst the current generation of new arrivals is not the only problem threatening the New Valley Project. Life has sprung out of the land here thanks to the vast Nubian sandstone aquifer, the largest source of fossilised water in the world and now the engine powering a huge land reclamation project. Yet despite already helping to cultivate almost two million new acres of desert since the 1950s, the aquifer’s reserves are finite and could run dry within 300 years. Alarmingly the water that does make it up to the surface is being squandered down unlined irrigation channels, which allow half of their precious cargo to drain away before it reaches the fields. Dr Jaskolski’s team are trying to raise awareness of conservation issues in such a fragile environment, but getting both residents and government agencies to think beyond the immediate future is a formidable challenge.

“That’s the whole issue with resettlement; rather than randomly moving as many people as possible out here you have to think about what sort of communities you want to create,” she says. “You have to provide the sort of service provision that will allow people to live sustainably. Right now, that’s absent. And the government, sadly, are trying to repeat Abu Minqar everywhere, because the problem of overcrowding in the Nile Valley isn’t going to disappear anytime soon – yet if we keep on wasting 50% of the water source then there’s no long-term future in the desert. As soon as the aquifer dries up we’re done here, everything and everyone is over.”

Yet as the desert evolves, the state’s presence in the lives of its people has a schizophrenic quality to it; it may be conspicuously lacking in Abu Minqar, but in other towns and villages it is entrenching itself in new and unfamiliar ways. In his book, Harding-King recounts many a happy evening spent with different omdas – local village mayors who ran their mini-fiefdoms with an uneasy autonomy from the oasis mamur, a colonially-appointed official from Cairo. The explorer variously described these figures as wise Solomons, corrupt nepotists or drunken fools, but the thread which held them together was the fact that they hailed from and lived in the villages they presided over, subject to close accountability from their people and possessing an unrivalled insight into the subtle dynamics of those communities. Today, the New Valley Project is slowly consigning omdas to the history books, as the Cairo-based government opens up new police stations run by officers from the Nile Valley.

Alongside the hilltop Turkish cemetery of Budkhulu and the breathtakingly sculpted dunes on the Ain Amur caravan trail, the Western Desert’s most beautiful spot must surely be the haunting ruins of Qasr Dakhla’s old city. When Harding-King stayed for several days in this thatch-covered labyrinth with its carved wooden doorways above and carpets of dust on the ground below it was a bustling market town; today everyone who can afford it has snapped up land in the new suburbs and left the ancient warren to an old groundskeeper and the occasional desert fox. Saleh Hassan is the last to have survived the exodus; his tiny little metal workshop, where handmade alfalfa scythes are churned out by a huge pair of bellows and a gleaming anvil, has stood here for generations. It would have been passed by Harding-King, back when Saleh’s grandfather owned the place. “These alleys used to be alive with people,” Saleh remembers. “Now they’ve trickled away.”

With them has gone the old political hierarchy of the town. Harding-King met the omda here a century ago and if you pay a visit to the little ethnographic museum on the edge of the old town you can follow the latter’s family tree all the way down through Mohammed, Mahmoud and Kamal, the step-brother of Fawzia Khala Hasaneen, who now runs the museum. “The omda was a man of the land, this land,” remembers Fawzia. “He understood our traditions; if there were any little problems and you could sit down with him face to face and sort them out. There was no need for the police.” There is now. Ten years ago Kamal was stripped of his title as omda as the government installed a public police station in the town and appointed an officer from Cairo. “The fact is there is less law and order now than there was back then,” Fawzia claims. “People are nervous about going to the police, so disputes today are left unresolved which damages the community.” Other villages are going the same way, as old power structures are swept aside in the name of Egypt’s future. “Everything has changed,” concludes Fawzia. “But then again, so have we.”

And therein lies the key to understanding this desert of contradictions, where nostalgia and the newfangled run hand in hand. Fear of something authentic, something real, being lost as the desert’s population evolves and technology stains the landscape is nothing new. Harding-King warned against the dangers of the motor car and the scouting plane for the desert; a century on, the Lonely Planet guide to Egypt boasts a similar distrust of modernity. The authors have nothing good to say about the town of Qasr Kharga, poster child for the government’s development plans, which has evolved in the space of a few decades from a quiet village to a major city of almost 100,000 people. Yet Kharga’s residents are delighted with the clean roads, neat flowerbeds and modern conveniences of recent years.

Nor is the desert’s engagement with modern Egypt is as linear as both Harding-King and Lonely Planet imply. Even as ‘modernity’ arrives it is challenged and shaped by local beliefs and customs stretching back thousands of years, reproducing a whole new identity for the desert which is always fluid. Young 4x4 drivers now take bookings from tourists over the internet and accept payment by credit card; at the same time, belief in the mystical ‘lost oasis’ of Zerzura – extensively documented by Harding-King – remains strong. So does a terror of afrits, evil spirits which will enter the body of those who step on them. Harding-King was dogged by afrits so persistently on his journey that he was forced to conjure up a ‘devilish English imp’ for protection in front of locals. Today, back in Qasr Farafra, Abdel Raba Abu Noor recalls a recent case where a Sheikh had to be summoned for 15 days of nonstop Quran recital in order to exorcise an afrit from one unfortunate villager. These customs, which Harding-King devoted entire appendixes to, are as integral a part of the modern Western Desert as its new phone masts; those that fetishise an imagined authentic past tend, like Harding-King himself, to be outsiders – doing so only for themselves. He may have set out in search of rock samples and ethnographic classifications, but the real lesson Harding-King unwittingly brought home was that any attempt to view the desert and its people through the prism of a musty museum display case is futile.

That doesn’t mean the dramatic transformation of this wilderness through the government’s grand programmes of land reclamation and mass resettlement shouldn’t be criticised where appropriate. For every success story rising out from the sand, like the 100 feddans of lush greenery that now burst out of the desert on Harding-King’s old route from Farafra to Dakhla – a nascent hops farm bursting with life on a stretch of land that was completely barren only two years ago – there are also the scattered relics of failure. Drive 40km south from Qasr Kharga and stare at the dunes on your left where the village of San’a once stood; peeking out of the ground are the long-deserted courtyards of houses now buried by dunes and telegraph poles knee-deep in ever-mounting sand. All of it was built by a government that tried to impose its own will on the desert and found instead that here the desert got the better of them. Further down the road is the desolate shell of New Baris, a much-vaunted project by visionary Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy in the 1960s, now also hemmed in by the dunes and standing forlornly as a monument to romanticism and over-ambition in this most painfully unromantic of environments.

A hundred years ago, Harding-King set off to explore a hidden corner of Egypt. Just like those who tried before him, he failed to make it to Kufara. But he did return – only just – to tell the tale, a tale of a ‘quaint’ way of life that was stuck in Egypt’s past. Today, as Omar Ahmed Mahmoud, Dakhla’s chief tourist officer, puts it, “We are Egypt’s future”. As dreams of the New Valley evolve slowly into reality, the only hope is that the desert peoples themselves are consulted and given a sufficient role to play in the changes that are revolutionising their homeland. “Everyone means well, there is no evil man here,” says Cassandra Vivian, author of the definitive modern-day guidebook to the area. “We must just give the locals a voice in the transition.” Those old enough to have heard first-hand stories of Harding-King’s amazing adventure into their desert concur. “Tradition is like time itself, it passes and we can’t stop that process,” says Sheikh Hassan Khalafala, a 78 year old from Rashda village in Dakhla. “So no, I don’t get sad about it. What can I do?”